Herodotus

had lived in the fifth century BC. Little is known about him beyond his

travels and books. His travels were extensive but not by modern

standards. At the time, the inhabited world, what the Greek called oikoumene,

was much smaller. On his travels he largely relied on secondary sources and

informants who were not always accurate. There is a big number of scholars who accuse him in lying about his travels. Some even say that he did not travel at all.

Despite all the criticism,

however, one thing that should definitely be noted about Herodotus is

his skilful depiction of fascinating and terrible events. Although not all of them have a historical background, they are indeed excellent sources for

understanding Herodotus' time and people. If you are interested, one

such story is of Harpagus, Median general who having disobeyed the King

Astyages was tricked into eating his own son.

Herodotus

describes Egyptian, Persian, Libyan, Babylonian and a few other food

cultures. Although he does not specifically lay out recipes or dishes we

can learn a lot from his writings.

Book One

Persia

133 And of all days their wont is to honour most that on which they were

born, each one: on this they think it right to set out a feast more

liberal than on other days; and in this feast the wealthier of them set

upon the table an ox or a horse or a camel or an ass, roasted whole in an

oven, and the poor among them set out small animals in the same way. They

have few solid dishes, but many served up after as dessert, and

these not in a single course; and for this reason the Persians say that

the Hellenes leave off dinner hungry, because after dinner they have

nothing worth mentioning served up as dessert, whereas if any good dessert

were served up they would not stop eating so soon. To wine-drinking they

are very much given, and it is not permitted for a man to vomit or to make

water in presence of another...

Things we can learn from these sentences on 5th century BC food culture (if we deem Herodotus' account trustworthy):

1. Persians were probably one of the first nations, if not first, to celebrate their birthdays.

2. Persians ate oxen, horses, camels and asses whilst no mention of pigs was made (perhaps accidentally).

3. Greeks did not have as sophisticated dinner courses and elaborate desserts as Persians.

4. Persians enjoyed drinking wine and made their wine most probably from grapes.

5. Persians had better "personal hygiene and table manners" than Greeks.

Babylon

193. ... They

use no oil of olives, but only that which they make of sesame seed; and

they have date-palms growing over all the plain, most of them

fruit-bearing, of which they make both solid food and wine and honey; and

to these they attend in the same manner as to fig-trees, and in particular

they take the fruit of those palms which the Hellenes call male-palms, and

tie them upon the date-bearing palms, so that their gall-fly may enter

into the date and ripen it and that the fruit of the palm may not fall

off: for the male-palm produces gall-flies in its fruit just as the

wild-fig does.

200. These customs then are established among the Babylonians: and there

are of them three tribes which eat nothing but fish only: and when

they have caught them and dried them in the sun they do thus,—they

throw them into brine, and then pound them with pestles and strain them

through muslin; and they have them for food either kneaded into a soft

cake, or baked like bread, according to their liking.

6. Babylonians used sesame oil instead of olive oil (no sunflower or vegetable oil is available yet).

7. Babylonians ate dates and made wine and honey from the dates.

8. Babylonians sun-dried fish, kept in brine, crushed and made cakes from it.

Book Two

Egypt

37. ... They [priests] enjoy also good things not a few, for they do not consume or spend

anything of their own substance, but there is sacred bread baked for them

and they have each great quantity of flesh of oxen and geese coming in to

them each day, and also wine of grapes is given to them; but it is not

permitted to them to taste of fish: beans moreover the Egyptians do not at

all sow in their land, and those which grow they neither eat raw nor boil

for food; nay the priests do not endure even to look upon them, thinking

this to be an unclean kind of pulse...

9. Egyptians did not eat beans as these were believed to be unclean.

47. The pig is accounted by the Egyptians an abominable animal; and first,

if any of them in passing by touch a pig, he goes into the river and dips

himself forthwith in the water together with his garments;

10. Egyptians did not eat or touch pigs.

77. ...and as to their diet, it is

as follows:—they eat bread, making loaves of maize, which they call

kyllestis, and they use habitually a wine made out of barley, for

vines they have not in their land. Of their fish some they dry in the sun

and then eat them without cooking, others they eat cured in brine. Of

birds they eat quails and ducks and small birds without cooking, after

first curing them; and everything else which they have belonging to the

class of birds or fishes, except such as have been set apart by them as

sacred, they eat roasted or boiled.

Note:

I have taken these extracts from G. C. Macaulay's translation of

Herodotus' books. Unless it had been employed in another sense, maize is

native to Americas and could not have been used by Egyptians in the V

century BC. I believe kyllestis was made from the emmer wheat that had a

special place in Ancient Egypt.

|

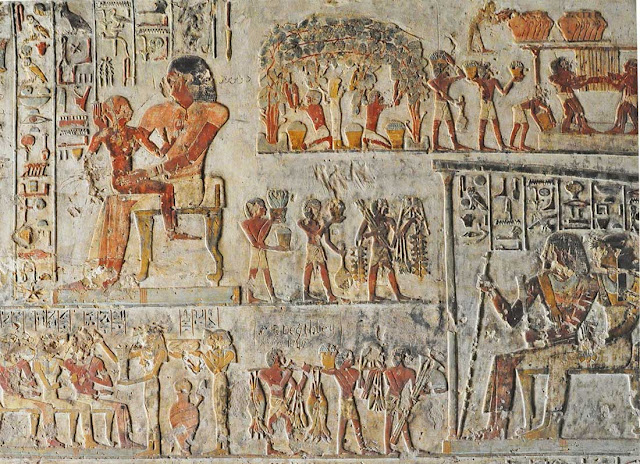

Ancient Egyptians cleaning poultry

From the tomb (TT52) of Nakht who was a scribe and

priest during the reign of Thutmose IV (1401 – 1391 BC ) |

|

|

11. Egyptian diet included grains such as emmer and barley.

12. Egyptians made loaves of bread and beer from grains.

13. Egyptians sun-dried or cured fish.

14. Egyptians cured certain birds and ate them without cooking.

92. All these are customs practised by the Egyptians who dwell above the

fens: and those who are settled in the fen-land have the same customs for

the most part as the other Egyptians, both in other matters and also in

that they live each with one wife only, as do the Hellenes; but for

economy in respect of food they have invented these things besides:—when

the river has become full and the plains have been flooded, there grow in

the water great numbers of lilies, which the Egyptians call lotos;

these they cut with a sickle and dry in the sun, and then they pound that

which grows in the middle of the lotos and which is like the head of a

poppy, and they make of it loaves baked with fire. The root also of this

lotos is edible and has a rather sweet taste: it is round in shape

and about the size of an apple. There are other lilies too, in flower

resembling roses, which also grow in the river, and from them the fruit is

produced in a separate vessel springing from the root by the side of the

plant itself, and very nearly resembles a wasp's comb: in this there grow

edible seeds in great numbers of the size of an olive-stone, and they are

eaten either fresh or dried. Besides this they pull up from the

fens the papyrus which grows every year, and the upper parts of it they

cut off and turn to other uses, but that which is left below for about a

cubit in length they eat or sell: and those who desire to have the papyrus

at its very best bake it in an oven heated red-hot, and then eat it. Some

too of these people live on fish alone, which they dry in the sun after

having caught them and taken out the entrails, and then when they are dry,

they use them for food.

Note: Lotus is rather a mysterious plant that ancient Greeks believed to cause "forgetfulness" (narcotic effect).

15. Some Egyptians made bread from lotus fruits in addition to eating lotus flowers, seeds and roots.

16. Some Egyptians baked and ate papyrus.

Book Three

India

98. ...Now there are

many tribes of Indians, and they do not agree with one another in

language; and some of them are pastoral and others not so, and some dwell

in the swamps of the river and feed upon raw

fish, which they catch by fishing from boats made of cane; and each boat

is made of one joint of cane. These Indians of which I speak wear clothing

made of rushes: they gather and cut the rushes from the river and then

weave them together into a kind of mat and put it on like a corslet.

17. Some Indians who wore clothing made of river rushes ate raw fish.

99. Others of the Indians, dwelling to the East of these, are pastoral and

eat raw flesh: these are called Padaians, and they practise the following

customs:—whenever any of their tribe falls ill, whether it be a

woman or a man, if a man then the men who are his nearest associates put

him to death, saying that he is wasting away with the disease and his

flesh is being spoilt for them: and

meanwhile he

denies stoutly and says that he is not ill, but they do not agree

with

him; and after they have killed him they feast upon his flesh: but

if it

be a woman who falls ill, the women who are her greatest intimates

do to

her in the same manner as the men do in the other case. For in

fact even if a man has come to old age they slay him and feast upon

him; but very few of them come to be reckoned as old, for they

kill every

one who falls into sickness, before he reaches old age.

18. Indians who were called Padaians practiced cannibalism.

100. Other Indians have on the contrary a manner of life as follows:—they

neither kill any living thing nor do they sow any crops nor is it their

custom to possess houses; but they feed on herbs, and they have a grain of

the size of millet, in a sheath, which grows of itself from the ground;

this they gather and boil with the sheath, and make it their food: and

whenever any of them falls into sickness, he goes to the desert country

and lies there, and none of them pay any attention either to one who is

dead or to one who is sick.

19. Some Indians who did not own houses or sow any crops lived on grains the size of millet, in a sheath.

Book Four

Libya

186. I have said that from Egypt as far as the lake Tritonis Libyans dwell

who are nomads, eating flesh and drinking milk; and these do not taste at

all of the flesh of cows, for the same reason as the Egyptians also

abstain from it, nor do they keep swine. Moreover the women of the

Kyrenians too think it not right to eat cows' flesh, because of the

Egyptian Isis, and they even keep fasts and celebrate festivals for her;

and the women of Barca, in addition from cows' flesh, do not taste of

swine either.

20. Egyptians did not eat the flesh of cows for religious reasons.

21.

Libyans who were nomads did not eat the flesh of cows and swine for

religious reasons but ate the flesh of other animals and drunk milk.

Summary

Among

the cuisines described by Herodotus the most sophisticated and

luxurious cuisine is that of Persians. Indeed, Persian cuisine was the

haute cuisine of the 5th century BC. The most of known world was not as

refined or cultivated and led an "uncomplicated" life. There was no

Roman Empire yet, Assyrian Empire was in ruins, Egypt was a satrapy

(province) of the Persian Empire and according to Herodotus himself, the

Greek lifestyle was not as sumptuous as Persian.

The

fact that Herodotus specifically mentions birthday feasts and certain

manners of Persians suggests that the Greeks and other nations known to

them, such as Egyptians, did not in fact give importance to birthdays and

did not regard lavatorial activities as a private matter. Persians

continued to have a splendid lifestyle and cuisine for many

more centuries. The nations that had managed to conquer them had also

adopted their luxurious way of life.

That

said, being among the oldest cuisines of the world Babylonian and

Egyptian cuisines should be noted for their food traditions and riches.

Herodotus' reference to Babylonian alternative of making oil from sesame

seeds rather than olives, and wine and honey from dates give us a hint

of the opulent cuisine of their once prominent empire. Ibn Battuta who

visited what is now Iraq in 1326-1327 also noted the date-palms and the

importance of dates in local populace's diet. He personally enjoyed the

honey (elsewhere) made from dates which he called sayalan (Waines, 2010).

Interestingly,

today the oldest surviving "cookbook" which consists of three cuneiform

tablets is Babylonian (they are referred to as Yale Culinary tablets

and kept at the Yale University in the US). On the whole, Ancient

Mesopotamia was well-known for its sophisticated cooking techniques and

cuisine. Their use of garlic, onion, dates, pistachios, sesame seeds,

fish and many other victuals were documented and preserved on a number

of ancient clay tablets. One such tablet written around 1700 BC, which

was actually a letter by a lady Huzalatum to her sister Beltani,

mentions the following foodstuff (Bottéro, 2004):

In

the last caravan I was brought 100 liters of barley semolina, 50 liters

of dates and 1.5 liters of oil; and they have just delivered 10 liters

of sesame seeds, and 10 liters of dates. In return, I am sending you 20

liters of coarse flour, 35 liters of bean flour, two combs, a liter of

siqqu-brine...There isn't any ziqtu-fish here. Send some to me, so that I

can make you some of that brine and can have it brought to you...

As

for the Ancient Egyptian cuisine, certain grains such as emmer and

barley played an important role in the lives of both poor and wealthy

Egyptians. The

kyllestis bread mentioned by Herodotus and the

beer made from grains were staples of all Egyptians. Interestingly, they

did not eat or touch pigs whilst animals such as cows and crocodiles

were deemed sacred and were not eaten at all. The Nile provided their

fish which they would prepare and eat in a variety of ways whereas some

of their fowl Egyptians would only cure.

Indeed,

Herodotus provides an interesting insight into the food culture of his

time. I recommend his book as an excellent guide for time-travelling to

the V century. It would be amazing to taste a Egyptian kyllestis bread, and date wine and honey, if these are still made.

Bibliography

Bottéro, J. (2004). The Oldest Cuisine in the World: Cooking in Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Herodotus (2008). The history of Herodotus — Volume 1 &2. Trans.

Macaulay, G. C. (George Campbell). The Project Gutenberg EBook of The

History Of Herodotus

Waines, D. (2010) The Odyssey of Ibn Battuta: : Uncommon tales of a medieval adventurer. London: I.B. Tauris.